Vincent Callebaut Architectures design features solar glass and urban farm.

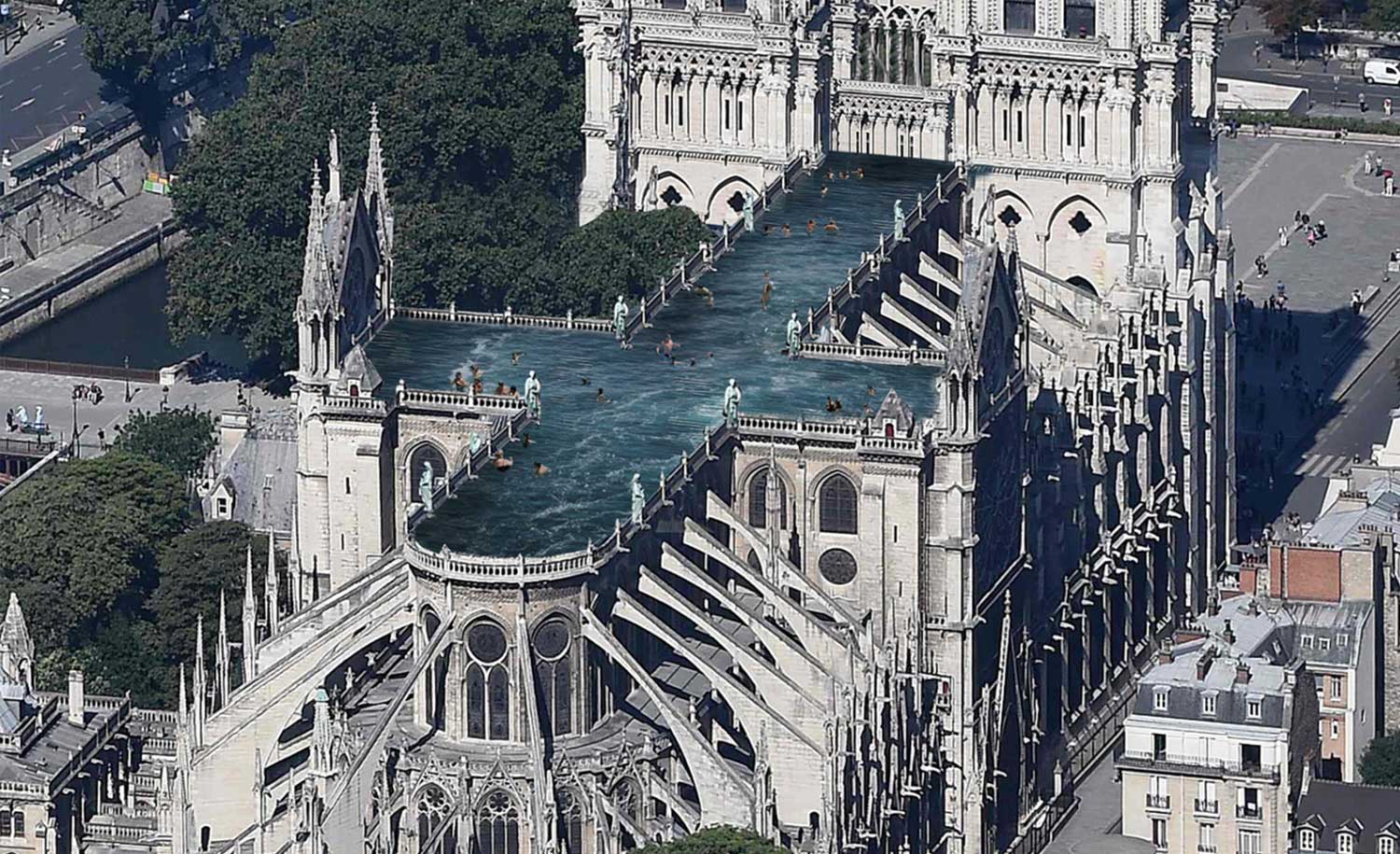

The potential redesign of the upper levels of the Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, after the destruction of a major fire in April, is attracting controversial proposals – such as a rooftop swimming pool, observation deck and sculpture of golden flames.

French Prime Minister Édouard Philippe, announcing an international design competition for the roofline, questioned if it was time to modernise any new additions to the UNESCO world heritage landmark.

“This is obviously a huge challenge, a historic responsibility,” he said, adding that the new design should be “adapted to technologies and challenges of our times.”

CM+ Design Director Richard Nugent considers how design can reconcile the past with the future by considering the original genesis of the building.

R.N.: What should we do with Our Lady?

The fire at Notre-Dame reverberated around the world. The shock of losing such an enduring part of our common architectural legacy has been felt by architects and non-architects alike. The reaction was immediate and intense.

The question of what to do next has arisen, from both groups, with the same intensity and immediacy. There is an understandable urge to ‘make it right’ and put back what was lost. This could be done, but will always be a facsimile of what once was. Anything we do will be a 21st century achievement.

While we often think of Notre-Dame as a purely medieval structure now more than 800 years old, it has always been an evolving work. Significant changes occurred as late as the mid-nineteenth century during a restoration effort that saw the spire added to the crossing.

While gothic architecture exhibits a distinctly recognisable style, it has always been much more than that. Gothic design is also the result of structural experimentation, pushing the limits of construction technology to achieve unprecedented height, lightness and airiness.

The flying buttresses foreshadow contemporary construction methods that separate enclosure from structure and allow large areas of glazing to radically transform the interior experience of architecture.

This urge to push limits sometimes resulted in overreach, such as the collapse of vaults at Beauvais Cathedral. The tower of Beauvais, prior to collapse, was the tallest structure in the world … almost 50 storeys … made largely of stone.

So let’s have a vigorous discussion about how to best make Notre-Dame whole again. While we do that we should remember that the spirit that created places such as Notre-Dame was not a timid one, afraid of experimentation. That spirit reached for the heavens, pushed technology and dared to soar.

We should be brave enough to be true to Notre-Dame. It deserves, still, to be the embodiment of that spirit … today, tomorrow and for at least another 800 years to come.

Some of the controversial proposals:

Designer Mathieu Lehanneur proposes a gleaming 300-foot flame made of carbon fiber and covered in gold leaf, in memorial to the tragedy. Image: Mathieu Lehanneur.

Open-air swimming pool by Stockholm studio Ulf Mejergren Architects, surrounded by 12 statues of the apostles that were removed from the roof before the fire. Image: Ulf Mejergren Architects